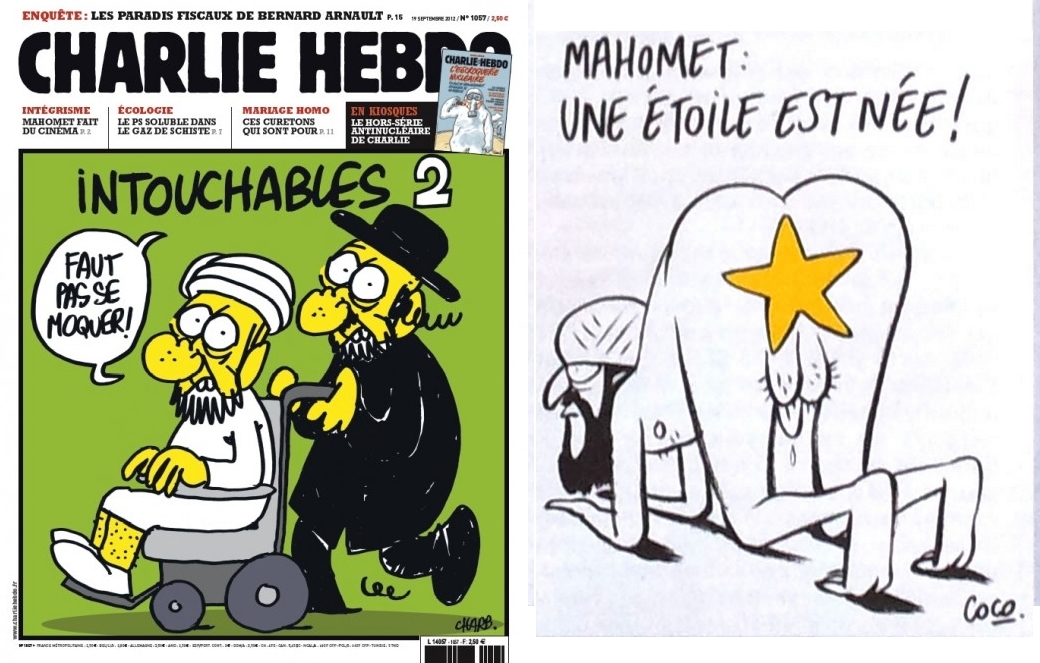

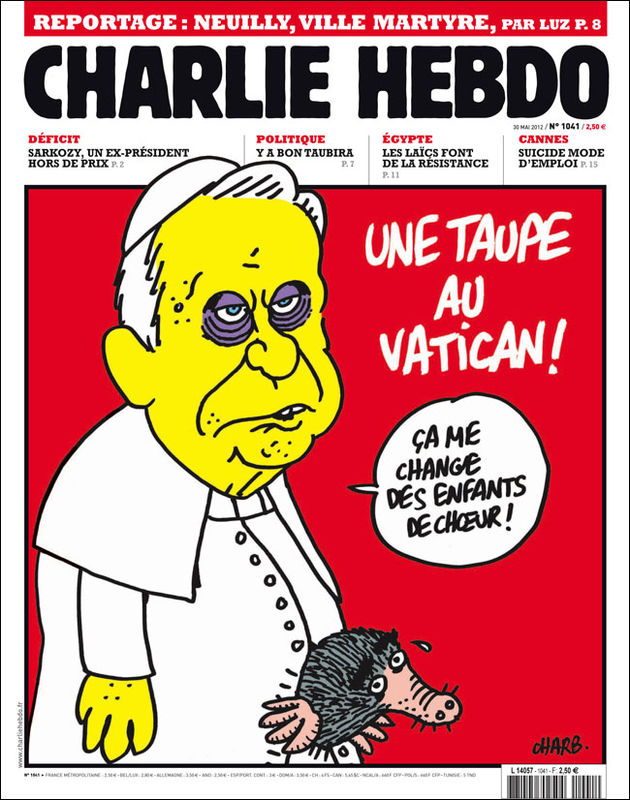

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo shooting, which left 12 people dead, the hashtag #jesuischarlie enveloped the internet. The attack, which took place in the Paris office of the satirical newspaper, was allegedly a response to the consistent profane imagery of the prophet Mohammed, construed under the guise of satire. Since the shooting, #jesuischarlie has been trending as people around the world rush to condemn violence and offer support for the slain journalists, as well as broader concepts deemed valuable in liberal democracies, including freedom of speech. Satire has the potential to act as effective social commentary, critiquing the status quo by skewering public figures. By definition, satire is meant to lampoon and draw attention to systems of power, power relations, and often, social injustice. Instead, Charlie Hebdo – a publication with a sordid history of Islamaphobia, xenophobia and homophobia – ridiculed a religious figure in a country where national rhetoric and policy are entrenched in Islamphobic sentiments and practice.

In a Salon article, Andrew O’Hehir writes that “the Paris attack was a direct assault on freedom”, Richard Dawkins tweets that Islam is “a religion of killers”, and Fox host Eric Bolling offers militarization as a response. What O’Hehir forgets to disclose is France’s own “direct assaults on freedom” – the civil war in C’ote D’Ivoire (2002), Operations Atalanta and Linda Nchi in Somalia (2009-present) and the 2014 Iraq offensive. In his tweet, Dawkins fails to note the culture of violence embedded in Western militaries and Bolling’s comments are a direct contradiction to evidence which confirms that over militarization does not act as a crime deterrant.  Following the media coverage of the shooting, some moderate Muslims flocked to the internet to denounce the shooting in an attempt to divorce the perception of violence as inherent to Islam, writing “As a Muslim, killing innocent people in the name of Islam is much, much more offensive than a cartoon will ever be”. A noble getsure, no doubt, but we need to question why such apologies are necessary. When Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people and injuring more than 600, moderate white men didn’t offer public apologies on behalf of the white patriarchy. McVeigh’s act of terrorism was not held as indicative or representative of his religious or ethnic communities. Communities grieved the loss of life and the attack on freedom, safety and liberty – but no national discussion was had about how violence informs white male Christian identity.

Following the media coverage of the shooting, some moderate Muslims flocked to the internet to denounce the shooting in an attempt to divorce the perception of violence as inherent to Islam, writing “As a Muslim, killing innocent people in the name of Islam is much, much more offensive than a cartoon will ever be”. A noble getsure, no doubt, but we need to question why such apologies are necessary. When Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people and injuring more than 600, moderate white men didn’t offer public apologies on behalf of the white patriarchy. McVeigh’s act of terrorism was not held as indicative or representative of his religious or ethnic communities. Communities grieved the loss of life and the attack on freedom, safety and liberty – but no national discussion was had about how violence informs white male Christian identity.  In the April 26, 1980 issue of The Nation Said wrote, “It is only a slight overstatement to say that Muslims and Arabs are essentially seen as either oil suppliers or potential terrorists. Very little of the detail, the human density, the passion of Arab-Moslem life has entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report the Arab world. What we have, instead, is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world, presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression.” When acts of violence are perpetrated by those conforming to the normative categories of what we are socialized to view as morally superior, ethnicity, race and religion are invisible. Discussions of ethnicity and religion are traded in for a more individualistic narrative: what could have possibly gone wrong? When acts of violence are committed by those who fall outside of these normative categories, those who are Othered, the narrative inevitably reflects onto the greater community in ways that vilification of whiteness and Christianity never do.

In the April 26, 1980 issue of The Nation Said wrote, “It is only a slight overstatement to say that Muslims and Arabs are essentially seen as either oil suppliers or potential terrorists. Very little of the detail, the human density, the passion of Arab-Moslem life has entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report the Arab world. What we have, instead, is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world, presented in such a way as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression.” When acts of violence are perpetrated by those conforming to the normative categories of what we are socialized to view as morally superior, ethnicity, race and religion are invisible. Discussions of ethnicity and religion are traded in for a more individualistic narrative: what could have possibly gone wrong? When acts of violence are committed by those who fall outside of these normative categories, those who are Othered, the narrative inevitably reflects onto the greater community in ways that vilification of whiteness and Christianity never do.  What happened in Paris was, no doubt, a tragedy. The loss of life is inexcusable, always. But what is needed now is a nuanced dialogue about the context in which this violent crime unfolded, an interrogation of our apathy, complacency and intolerance – not widespread condemnation of Islam. I am not Charlie – and neither are you.

What happened in Paris was, no doubt, a tragedy. The loss of life is inexcusable, always. But what is needed now is a nuanced dialogue about the context in which this violent crime unfolded, an interrogation of our apathy, complacency and intolerance – not widespread condemnation of Islam. I am not Charlie – and neither are you.

Further links

Millions Attend the Rally showing Solidarity for the Slain Journalists – Aljazeera

Nicolas Kristof asks if Islam is to blame for the shootings at the Charlie Hebdo Office – New York Times

Asghar Bukhari argues that the attack had nothing to do with free speech, but derives from war – Medium.com

How the far right and conservatives in Europe responded to the Charlie Hebdo shootings – Vice.com

A profile of the slain victims of the Charlie Hebdo shootings. – BBC.com

Khaled Diab discusses whether the Prophet Muhammad would say ‘Je suis Charlie’ – Aljazeera

“One of the stranger aspects of the tragedy is the way in which solidarity with Charlie Hebdo, a publication not known for its conservatism or subtlety, has been effusively expressed by the kind of people with whom its staff would have struggled to empathize” – Legendary Cartoonist Ralph Steadman speaks